Surgeons at the University of Michigan’s CS Mott Children’s Hospital (Ann Arbor, Mich) have successfully implanted 3-D printed tracheal splints to open the collapsed airways of an 18-month-old boy, according to the university.

The child is the second infant whose life has been saved with the new, bioresorbable airway splints that were created using a biopolymer called polycaprolactone. Another child was saved using the procedure in May 2013.

The second child suffered from a condition known as tetralogy of Fallot with absent pulmonary valve, which can put tremendous pressure on the airways, according to U-M. The boy developed severe tracheobronchomalacia, or softening of his trachea and bronchi, and his airways collapsed to the point that they were reduced to small slits.

For months, the child would stop breathing and turn blue, sometimes four to five times a day, according to his mother. As a result, medical personnel had to resuscitate him with heavy medication or other interventions.

According to doctors at U-M, the child needed to be on a ventilator at pressure levels that had reached the maximum, and he was not improving. What’s more, he was often on strong medication and even had been put into a medically-induced coma because he would work against the ventilator if he was awake.

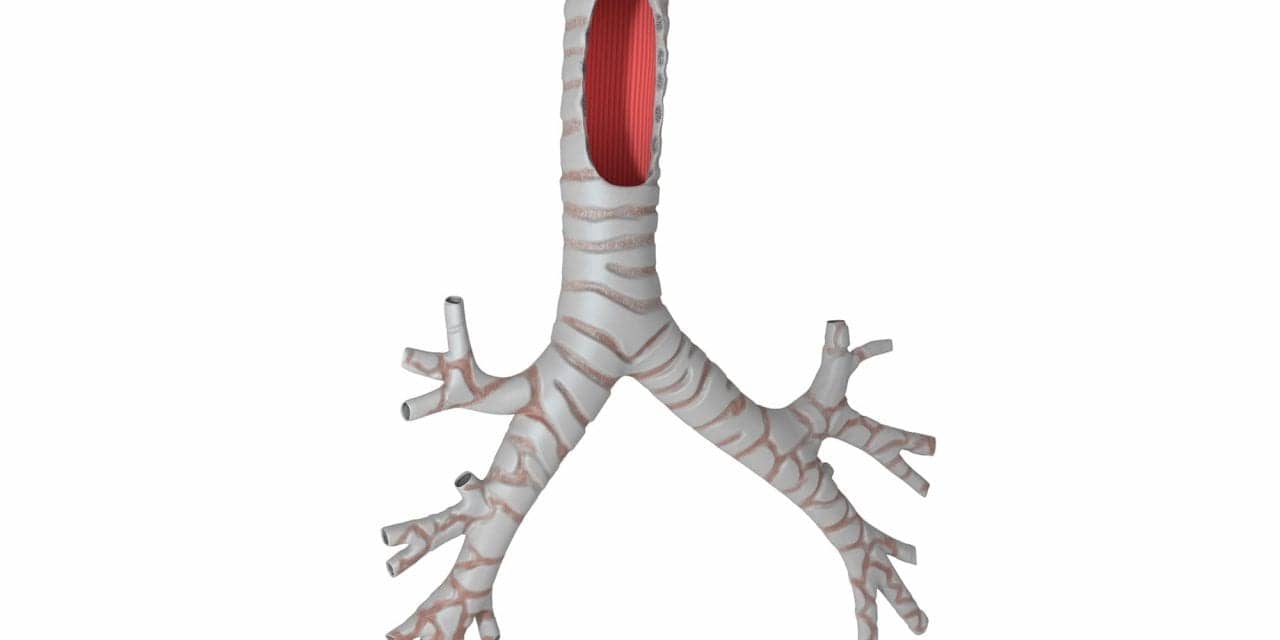

Using their procedure that saved the previous patient, University of Michigan doctors Glenn Green, MD, and Scott Hollister, PhD, took a CT scan of the boy’s trachea and bronchi and integrated an image-based computer model with laser-based 3-D printing to produce the splint, which was custom fit within the baby’s airway.

Assisted by Green, pediatric surgeons sewed two splints around the boy’s right and left bronchi to expand the airways and give it external support to aid proper growth.

The bioresorbable splints have successfully improved the child’s breathing, enabling less ventilator support and allowing the boy to go home for the first time. According to the University, in the course of 3 years, the splint will be naturally reabsorbed by the body.

“It is a tremendous feeling to know that this device has saved another child,” said Hollister. “We believe there are many other applications for these techniques, but to see the impact living and breathing in front of you is overwhelming.”

According to U-M, severe tracheobronchomalacia is rare. About 1 in 2,200 babies is born with tracheobronchomalacia, and most children grow out of it by age 2 or 3, although it often is can be misdiagnosed as asthma that doesn’t respond to treatment.

“Severe tracheobronchomalacia has been a condition that has frustrated me for years,” Green added. “I’ve seen children die from it. To see this device work, for a second time, it’s a major accomplishment and offers hope for these children.”