Children with a rare form of muscular dystrophy called Pompe disease often spend their days tethered to mechanical ventilators in order to breathe. But results from a new clinical trial at University of Florida Health show that gene therapy improved respiratory function in these patients and increased the time they could spend breathing on their own without assisted ventilation, according to research published online ahead of print in the journal Human Gene Therapy.

Pompe disease is a neuromuscular condition that occurs when children are born with mutations in a gene responsible for the production of an enzyme called lysosomal acid alpha-glucosidase, or GAA. The enzyme is necessary to convert stored sugar in the body to glucose. Without it, the stored sugar, or glycogen, builds up in muscle. This accumulation leads to muscle weakness and damage that affects patients’ ability to walk and breathe, and can ultimately harm the heart, according to researchers.

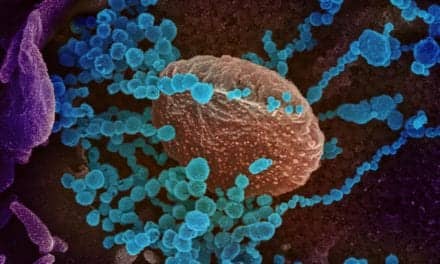

For the clinical trial, researchers injected patients with a corrective form of the gene using the vector adeno-associated virus type 1, or AAV-1, a harmless virus that shuttles the gene directly into cells. All of the patients the researchers followed for the first year of the study continued to improve. Specific improvements varied; some patients were able to breathe on their own for additional minutes while others were able to make it an hour or more without using a ventilator.

“The ultimate hope is if we can intervene earlier in their disease process, we will be able to maintain or improve their function even more,” said co-author Barbara Smith, PT, PhD, an assistant professor of physical therapy in the UF College of Public Health and Health Professions whose additional abstract recently earned her an Excellence in Research Award from the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy. “That’s our goal.”