Respiratory devices such as NIV masks, ETT/tracheostomy devices and holders, and nasal cannula can cause pressure injuries to patients. A study by researchers at Baptist Medical Center–Jacksonville found that a targeted intervention implemented within its RT department successfully prevented respiratory device-related pressure injuries in acutely ill patients.

By Joan Holdman, MS, RRT; Cathy Rozansky, DHSc, RRT; and Tammy Baldwyn, RRT

It is estimated that $11 billion is spent annually in the United States on pressure injuries, with the average cost per injury being $500-$70,000.[1] When the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) changed reimbursement rules in 2006, hospital-acquired pressure injuries became a priority for hospitals because CMS saw pressure injuries as a preventable injury for inpatients. CMS deems Stage 3 and Stage 4 pressure injuries to be preventable while admitted as inpatients to medical facilities.[2]

Pressure ulcers are a real concern to acute and long-term care facilities because they increase morbidity, cost of care, and decrease reimbursement. In addition, the presence of these injuries can cause pain for the patient and emotional distress, not only for the patient but also for their family.[3]

Respiratory devices such as noninvasive ventilation (NIV) masks, tracheostomy devices, nasal cannulas, endotracheal tubes (ETT), and ETT holders or tape can cause pressure injuries to patients. Pressure injuries can make it uncomfortable for patients on NIV to wear a mask around the clock if required; they can also make it uncomfortable for patients to wear a nasal cannula.

In two different studies, medical device pressure injuries have been shown to occur in 24% to 34.5% of patients and, of those, 30% to 70% were caused specifically by respiratory-related medical devices, especially in critical care units.[4] For intubated patients that are secured with tape, it is difficult to evaluate them for mucosal injury so commercially available securement devices should be used.[5] This also makes it easier for ETTs to be moved on a more regular and frequent basis.

At Baptist Medical Center (Jacksonville, Fla), there had been an increase in pressure injuries from respiratory devices documented in the healthcare system’s adverse events reporting system.

Methods

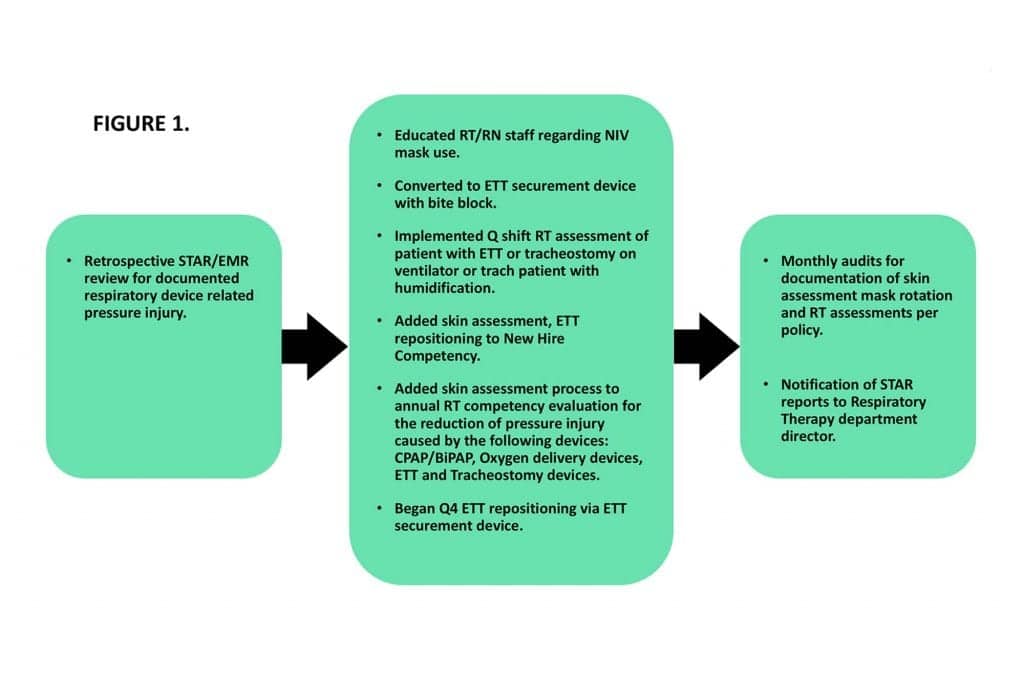

Noting an increase in pressure injuries from respiratory devices reported into the Safety Trending and Reporting System (STAR), there was the development of a plan to reduce the incidence of these pressure injuries in the future. The root cause analysis determined that non-invasive ventilation (NIV) mask interfaces, heated-high flow nasal cannula (HFNC), endotracheal tubes (ETT) and bite blocks, tracheostomy devices, skin barriers, staff knowledge regarding pressure injury, lack of staff training on skin assessment, and lack of documentation were primary causes. Of note, NIV is used at an increased frequency or first choice support for respiratory distress versus intubation as in previous decades.

The facility interventions were as follows:

- Education of respiratory therapists (RT) and registered nurses (RN);

- Use of skin barrier was terminated and converted to an ETT securement device with a built-in bite block.

- RTs became responsible for the following: once-per-shift respiratory assessment of patient with ETT or tracheostomy on a ventilator or tracheostomy patient with humidification, rotation of NIV masks from nasal to full-face every four hours, and ETT repositioning every four hours.

- Additionally, RTs (along with RNs) were made responsible for documentation of skin assessment, documentation of leak for NIV patients, and documentation of oral assessment for intubated patients. Oral assessments on ventilator patients were performed every shift by both the RT and RN together at the patient’s bedside.

- Education was also added to new hire orientation for both RNs and RTs, as well as an annual competency requirement for both disciplines.

The development of this plan had a goal of reducing the occurrence of pressure injuries to less than four per year. Monthly chart audits were performed to verify documentation of the aforementioned interventions. (See Figure 1.)

This study was a prospective interventional single-arm quasi-experimental study. Data was gathered for two months (February to March 2019). Data was extracted from the EMR as well as the health system’s STAR system. Data was entered into the EMR on each patient by the attending RT or RN. STAR data was entered if any of the included patients developed a pressure injury at that time, and the wound care nurse was consulted for appropriate care of the pressure injury.

All intubated ICU patients >18 years of age were enrolled, as were patients receiving NIV acutely. Patients that are intubated had their ETTs secured with the commercial ETT securement fastener with a built-in bite block. These ETT fasteners are already part of the hospital supply-chain. Patients receiving heated high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) therapy or humidification for tracheostomy were also included for review.

Results

During the two-month study period, 30 chart audits were performed each month (n=60). Patients were either on a ventilator via ETT or trach tube (n=34), on NIV (n=7), on HFNC (n=7) or receiving humidification via tracheostomy mask (n=12). Documentation of skin integrity (NIV) was found to occur 57% of the time, NIV leak was documented 57% of the time, mask rotation occurred 71% of the time, joint RT/RN ETT oral assessment was documented 100% of the time, ETTs were repositioned per policy 84% of the time, and RT assessment every shift on study patients were completed 72% of the time. Zero pressure injury was reported during the study period.

When this data—specifically the pressure injury data—is compared with the same time period in the previous year, there is a decrease of pressure injuries (2018 n=1; 2019 n=0). Calendar year data review shows the following for respiratory device-related pressure injury at the study institution: 2016 (n=5), 2017 (n=8), 2018 (n=4). This data analysis shows a significant difference in pressure injury after intervention during the time period of December 2017 through August 2018.

Discussion

Our findings reveal that implementing a multidisciplinary plan that includes education, bedside assessment by both caregivers (RT and RN), and movement of respiratory devices can reduce pressure injuries.

To our knowledge, no other pressure injury studies have included ETT, NIV, HFNC and tracheostomy devices. A 2017 study[6] compared mask pressures on the bridge of the nose and found that a particular brand of oro-nasal mask exerted less pressure on the bridge of the nose compared to two other oro-nasal masks and one other nasal mask. In addition, a 2018 study[7] looked at NIV with and without humidity and skin breakdown; it found that humidity played no role in interface pressures. A 2013 article by Hess[8] states that the “first choice of interface should be the oro-nasal mask…and a total face mask might also be a reasonable first choice for interface.”

In our study, we rotated masks every four hours between a nasal mask and an oro-nasal mask; future studies may want to research the advantage of rotating oro-nasal masks with total face masks.

In regard to pressure injury caused by endotracheal tubes, a 2017 study[9] investigated the occurrence of pressure injury when the taped ETT was moved every third day. Patients experienced a 13% incidence of pressure injury (n=5/38), however, these patients experienced worsening oral condition as a result. The study concluded that ETTs may need to be moved more frequently than every third day.[9]

An additional 2018 study[10] in Australia found that using a securement device similar to the one in our study (no built-in bite block) increased their incidence of pressure injury significantly (16 pre-intervention vs 36 post-intervention). A 2017 study[11] in a single-center ICU determined that 27.9% of patients developed a medical device-related pressure injury (MDRPI). Of those, oxygen tubing (behind the ears) and ETT were the most common types of devices to cause pressure injury.

We closely reviewed a 2018 study[1] that involved NIV mask pressure injury in particular. The policy changes for this study, however, also involved implementing an algorithmic protocol to allow for quicker liberation from NIV as well as more realistic adjustments in settings. Clinicians also performed daily rounding on all NIV patients to ensure adherence to the protocol. This study noted a 79% decrease in NIV mask pressure injury (24 vs 5).[1] The liberation protocol, as well as the daily rounding, may have also contributed to their decreased incidence of pressure injury.

Furthermore, we reviewed a 2017 study[4] that also included interdisciplinary collaborative rounding on patients receiving NIV, as well as patients that were intubated and on ventilators. The remainder of their interventions were similar to what we introduced and they saw their MDRPIs decrease from 8 to 5 (2 NIV injuries occurred before the planned interventions were put into place).[4]

In addition to following some of these study protocols, we also consulted the pressure injury prevention bundle that was set forth by The Children’s Hospitals Solutions for Patient Safety Network.[12] The bundle included rotation of devices and skin assessment. We also followed the securement device manufacturer guidelines for routine repositioning of the ETT.[13]

Conclusion

In this limited pilot study we found that education, mask rotation, ETT repositioning, and documentation combined to reduce the incidence of respiratory device-related pressure injury. This study was time-limited and should be studied further.

Recommendations

- Utilize respiratory therapist weaning protocols in order to eliminate extended use of respiratory devices when patient condition indicates weaning of therapy.

- Implement RT department annual education on respiratory device-related pressure injury and prevention strategies.

- Create or revise department policy for respiratory devices utilized following evidence-based practice recommendations.

- Develop an audit tool based on respiratory device utilization per institution for policy compliance.

- Provide targeted education based on institution audit results for respiratory therapists.

- Initiate a performance improvement project and determine how looking back at data can improve future outcomes.

RT

Joan Holdman, MS, RRT, is director of Clinical Education, Respiratory Therapy Program, St John’s River State College, St Augustine, Fla.

Cathy Rozansky, DHSc, RRT, is manager of Adult/Pediatric Pulmonary Care and Pulmonary Function Laboratory Departments at Baptist Medical Center–Jacksonville and Wolfson Children’s Hospital, Jacksonville, Fla.

Tammy Baldwyn, RRT, is supervisor of Adult Pulmonary Care Department at Baptist Medical Center-Jacksonville, Jacksonville, Fla.

The author’s would like to acknowledge the respiratory therapists of Baptist Medical Center–Jacksonville’s Adult Pulmonary Care Department for their participation in this study.

References

- Boyko TV, Longaker MT, Yang GP. Review of the current management of pressure ulcers. Adv Wound Care. 2018;7(2):57-67.

- Zaratkiewicz S, Whitney JD, Lowe JR, Taylor S, O’Donnell F, Minton-Foltz P. Development and implementation of a hospital-acquired pressure ulcer incident. J Health Qual. 2010;32(6):44-51.

- Miller K, Cascioli L, Harter C, Kermalli M. A multidisciplinary approach to reducing pressure injuries during noninvasive ventilation. RT for Decision Makers in Respiratory Care. 2018; May/June:18-22.

- Padula CA, Paradis H, Goodwin R, Lynch J, Hegerich-Bartula D. Prevention of medical device-related pressure injuries associated with respiratory equipment use in a critical care unit. A quality improvement project. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2017;44(2):138-141.

- Zaratkiewicz S, Teegardin C, Whitney JD. Retrospective review of the reduction of oral pressure ulcers in mechanically ventilated patients: A change in practice. Crit Care Nurse Q. 2012;35(3):247-254.

- Brill AK, Pickersgill R, Moghal M, Morrell MJ, Simonds AK. Mask pressure effects on the nasal bridge during short-term noninvasive ventilation. ERJ Open Res. 2018;4:00168-2017.

- Alqahtani JS, Worsley P, Voegeli D. Effect of humidified noninvasive ventilation on the development of facial skin breakdown. Respir Care. 2018;63(9):1102-1110.

- Hess D. Noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Respir Care. 2013;58(6):950-972.

- Wickberg M, Falk AC. The occurrence of pressure damage in the oral cavity caused by endotracheal tubes. Nord J Nurs Res. 2017;37(1):2-6.

- Hampson J, Green C, Stewart J, Armistead L, Degan G, Aubrey A, et al. Impact of the introduction of an endotracheal tube attachment device on the incidence and severity or oral pressure injuries in the intensive care unit: A retrospective observational study. BMC Nurs. 2018;17:doi:10.1186/s12912-018-0274-2.

- Barakat-Johnson M, Barnett C, Wand T, White K. Medical device-related pressure injuries: An exploratory descriptive study in an acute tertiary hospital in Australia. J Tissue Viability. 2017;26:246-253.

- Frank, G, Walsh, KE, Wooten, S, Bost, J, Dong, W, Keller, L, et al. Impact of a pressure injury prevention bundle in the solutions for patient safety network. Pediat Qual Saf 2017, 2:e013: doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000013.

- Hollister Education. Anchorfast oral endotracheal tube fastener device care tips. http://www.hollister.com/en/criticalcare/criticalcareprofessionalresources. Accessed February 1, 2019.