The department of respiratory care services at Duke University Medical Center carries out the hospital’s dedication to patient care, research, and education.

For the physicians and staff of the Department of Respiratory Care Services at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, being part of a major university hospital provides numerous opportunities to gain experience and expertise in standard respiratory care cases—as well as in the more unusual ones.

Respiratory supervisor provides tips on airway management technique.

Respiratory supervisor provides tips on airway management technique.

Because of Duke’s reputation as a top hospital in care and research, the respiratory care department handles a large volume of patients. Duke is licensed for approximately 1,000 beds, and approximately 55% of patients admitted to the hospital receive some form of respiratory care.

“Respiratory is part of what we call the Duke health system,” says Neil MacIntyre, MD, medical director of respiratory care. “The medical center likes to think of itself as a triple threat: It provides outstanding patient care, research, and education.”

“We [in the respiratory care department] support each of those aspects of the mission through our scope of practice,” adds Robert Campbell, MBA, RRT, RCP, clinical manager of the department.

Respiratory care services at Duke started in 1965 with Houston R. Anderson, a former military corpsman who started the first school in North Carolina for respiratory care—a hospital-based education program that eventually expanded to community college campuses.

At Duke, Anderson set up the respiratory care services department as a division of anesthesiology and became the director. Later on, respiratory care services became a freestanding department, with medical direction coming out of anesthesiology. In 1981, MacIntyre became the department’s medical director.

The department, which now reports to senior leadership through the Heart Center, includes 110 full-time employees; of those, 92 are clinical employees. About 95% of the clinical staff members are registered respiratory therapists, a requirement to work in the hospital’s intensive care units.

Respiratory care practitioners provide services 24 hours a day to patients in the hospital’s critical care and intermediate care areas. To best meet patients’ needs, RCPs are assigned to either the adult or pediatric clinical team, which helps develop expertise in patient assessment, as well as an understanding of disease management for the population of patients they serve.

The adult clinical team serves patients in the critical care areas of the emergency department, surgical intensive care, medical intensive care, cardiothoracic intensive care, coronary care, and neurosciences intensive care, as well as patients in the adult bone marrow transplant, pulmonary step-down, and intermediate care units.

The pediatric clinical team serves patients in the pediatric intensive care unit, intensive care nursery, pediatric bone marrow transplant unit, and pediatric step-down, as well as intermediate care units. Within the pediatric clinical team, a group of respiratory care practitioners are trained as ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) specialists.

The respiratory care staff is divided into three groups: core-team individuals who are assigned to specific intensive care units; intensive care float-pool individuals who subsidize the core-team members; and intermediate care individuals who cover intermediate and general care.

A core team of respiratory care practitioners is assigned to each of the adult and pediatric critical care areas/units and works in the same critical care unit each day. “The core teams in the intensive care units were started a number of years ago for consistency and for the development of experts and to be the face for the respiratory care department to the multidisciplinary team. The people in those units help formulate the plan of care for the patients, along with the rest of the members of the team,” Campbell says.

“A selling point for our department from the therapists’ perspective is the level of respect that we get from the physicians’ staff, and the amount of interaction that we have with the physicians, plus the ability to do a lot of different [procedures]. I think that is what keeps many people here. It’s a nice variety,” adds Janice Thalman, RRT, MHS, FAARC, director of respiratory care services.

The scope of respiratory care practice includes administration of inhaled aerosol medications—approximately 110,000 inhaled aerosol procedures are performed annually; oxygen and medical gas therapy, including specialty gases such as nitric oxide and heliox; noninvasive positive pressure ventilation; tracheostomy care; mechanical ventilation management by protocol—the department averages approximately 60 ventilations per day in the adult and pediatric units; airway management/intubation; arterial blood gas puncture; radial artery cannulation; and bronchoscopy assist.

“Other respiratory departments do some of these things—we do all of them. Our scope is very broad,” Thalman says. “That helps us with recruitment, and it also helps with keeping enthusiasm high because the learning curve is high here.”

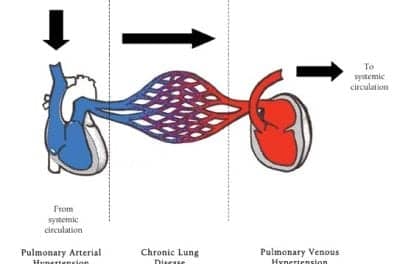

The respiratory care department also has world authorities on such diseases as interstitial fibrosis, cystic fibrosis, and pulmonary hypertension. In addition, Duke is one of the world’s largest lung transplant centers. “Duke is a referral point for more specific types of diseases, so we get a lot of patients with end-stage diseases that might qualify for lung transplants,” MacIntyre says.

Duke was also one of the centers in the National Emphysema Treatment Trial, looking at lung reduction surgery, and is one of the centers of the ARDS Network, which was established by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, to hasten the development of effective therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome.

“We tend to get referrals for severe ARDS. We not only put them on the protocol, but we’re one of the largest users of high-frequency ventilation,” MacIntyre says.

Another unique aspect of working at Duke is that the department’s respiratory care practitioners are also involved in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) cases. Patients with PAP, a rare lung disorder in which the alveoli fill up with surfactant, are treated using whole lung lavage, a procedure performed by the hyperbaric medicine department. Following the procedure, patients recover in the medical intensive care unit. Postprocedure care, which includes mechanical ventilation management and extubation, is the role of the respiratory care staff.

In addition to treating patients, the respiratory care services department is also involved in research. Current research projects include evaluating monitors of work-of-breathing and power-of-breathing in animal studies, developing new devices for the delivery of aerosols to intubated patients, and looking at new ways of providing vasodilator therapy as an aerosol.

Duke receives funding for its research from various sources, including foundations, industry, and NIH contracts. Two respiratory therapists on staff are dedicated full-time to obtaining grants and contracts.

Members of the respiratory care department also support the education of physicians, nurses, and other members of the medical team by participating in patient care rounds and providing lectures, demonstrations, and workshops.

“The two things that I’ve been most proud of in my 20-some years here working with this group is the development of our advanced practitioners … and the involvement in the development of new things—a lot of our therapists get involved in research projects, ranging from simple evaluations of new gadgets to actually participating with companies in the development of new technologies, and being involved in large clinical networks. They get involved in this cutting edge work, and I think that’s been one of the special things about this place,” MacIntyre says.

“You’ve got to have the resources that can build new programs, that can invest in new projects and serving new patient populations, and that can provide the research infrastructure that often is required to get programs like these going,” he says. “These kinds of things can’t be done at community hospitals. You need a big research-focused, educationally focused academic center that is willing to put resources into it.”

Danielle Cohen is a staff writer for RT.