Facility preparedness for the rare but real risk of a Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) patient is a smart policy, say experts on the virus.

By Greg Thompson

It is an ordinary Thursday night in May. A man walks into your hospital’s emergency department seeking treatment for severe acute respiratory illness. The reception staff directs him to the waiting room. Later, while being examined, he discloses that 10 days prior to seeking treatment, he had arrived from Saudi Arabia where the coronavirus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) has infected hundreds of people.

Could this scenario happen at your facility? It did this past summer at Orlando Health’s Dr. P. Phillips Hospital, a not-for-profit hospital in Orlando.

“This can show up anywhere at any time, so you just have to be prepared for it,” says Eric Alberts, head of Emergency Preparedness for Orlando Health.

Fortunately, when the patient with MERS-CoV arrived, Dr. P. Philips Hospital was already on the lookout for the virus because Community Hospital in Munster, Ind, had seen the first US MERS case just a week before. In addition, thanks to the efforts of Alberts in pushing for a MERS drill the previous Summer, hospital staff memebers had already practiced what to do when a potential MERS patient arrives.

“We were lucky it was the same disease as we had drilled for,” says Antonio Crespo, MD, head of the Infectious Diseases Department and chief quality officer for Dr. P. Phillips Hospital. “That almost never happens. The idea of the exercise is to be ready when anything happens, but in this case, it was the same disease. I think it helped a lot in terms of when the infection preventionist was called.”

Staying up to date on infectious diseases, teaching care teams (including respiratory therapists) how to quickly identify and isolate patients that seem suspicious, and finally educating everyone on when and where to call for help is reinforced with real-life drills.

Crespo says that because of the drill his hospital had conducted, when the real MERS-CoV patient presented, the transmission of information from the initial care team to infection prevention, state and federal health agencies, and hospital administration was smoother. He got the call the very next morning about the patient and was able to immediately look up the patient’s electronic health record and contact Florida’s Orange County Health Department for guidance on testing. A 20-person conference call with the CDC was held later the same day.

Remote but Real Risk

The first occurrence of MERS-CoV was documented in June 2012 in a 60-year old male who died in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.[1] Since then, 938 laboratory-confirmed cases of infection with MERS-CoV have been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), including at least 343 related deaths, according to a Dec 17 WHO report.[2] Of the total, 821 cases have been confirmed in Saudi Arabia. The Kingdom claims a total of 355 deaths due to the virus, according to a Dec 17 report from its Ministry of Health.[3]

Although the virus is relegated almost exclusively to the Middle East and surrounding regions, it is by no means quarantined. In our modern world, a pathogen like the coronavirus that causes MERS can travel with its human host to a community before the infected person even knows he or she is sick. Respiratory therapists working in US hospital emergency departments may be among the first to encounter and detect the disease. However, because MERS is poorly understood and can cause a range of symptoms from relatively mild to deadly, a MERS patient is not out of the question in any care setting where respiratory illness is treated.

“All healthcare professionals, including respiratory therapists, should follow Centers for Disease Control guidance on the MERS website,” wrote Darlene M. Foote, a CDC public affairs specialist, in response to questions from RT Magazine. “They should be able to identify patients who should be evaluated for MERS infection; report these patients to their state or local health department; and adhere to recommended infection control measures, including standard, contact, and airborne precautions.”

Although the Joint Commission requires accredited facilities to prepare for a mass infectious disease event, facilities do vary in their individual level of preparedness, Alberts says. In addition to reviewing the CDC’s preparedness checklist at as well as the World Health Organization’s most current information, consider drills to test your own facility’s preparations.

Alberts relied heavily on the CDC information when planning the drill at Dr. P. Philips Hospital and says that it was one of the best drills he’d ever organized because of the involvement he got from local government agencies that work with Orlando Health on regular hazard vulnerability analysis. In July of 2013, the hospital administration, along with local fire rescue, law enforcement, emergency preparedness and health agencies had done a table-top exercise. This was followed by an August of 2013 full-scale exercise.

Part of the reason Dr. P. Philips Hospital ranks the threat of mass infectious disease so highly is that it is one of the closest hospitals to the major Orlando tourist destinations of Disney World, Sea World, Universal Studios and the convention center, Alberts and Crespo say. However, any healthcare provider may potentially see a MERS patient.

“The lessons learned from this drill were huge, not only recognizing the threat as real but also what we had to do within the hospital when triaging patients,” Alberts says. “One of the questions our folks were not used to asking at the time was ‘Have you traveled?’ So after that they stared asking those types of questions.”

Should clinicians forget, there is now a reminder that has been added to the hospitals EHR that prompts them to ask about travel history.

Preparing for the Unexpected

Dr. P. Phillips Hospital drilled MERS-CoV in 2013 because, at the time, the mortality rate for MERS was thought to be as high as 50%. “People were pretty scared about it,” Alberts says.

Today, an Ebola hemorrhagic fever drill may be more likely, but any infectious disease drill can help in getting ready for the real thing. Indeed, Dr. P. Phillips Hospital is using some of what it learned from treating a MERS patient in its efforts to prepare for Ebola, Dr. Crespo says.

“One of the big things we learned during the exercise was that our infection control and prevention folks had to be there engaged and proactive in the response to this situation,” Alberts says. He adds that after the drill, the hospital made it a practice to station a member of the infection control team outside an isolation room to monitor infection control precautions such as tracking of staff and visitors entering the room, donning the appropriate protective clothing and adhering to hand washing protocols.

Is the Risk Increasing?

Two things could be making zoonotic diseases such as Ebola, MERS and the related coronavirus disease SARS an increasing concern, notes Kevin Olival, PhD, a senior research scientist at EcoHealth Alliance, and an expert on MERS-CoV. The first is that deforestation and other man-made environmental changes are bringing humans and animal populations into closer contact and allowing transmission of more animal diseases to humans. The second is that once a disease in another species jumps to humans, it may spread much more rapidly because of modern mass transportation.

“I think something could happen in any part of the world,” he says. “I think there are definitely airports and regions that are going to be more risky just based on the number of travelers coming through, and we’ve done some mapping of this based on global travel to the Middle East and back. But if you try to map that to hospitals, you might give a false sense of security to other hospitals because you never know. People can travel at will around the world and even in a small town, somebody may go to Saudi Arabia for business and they may come back infected, so I wouldn’t rule anything out.”

MERS is a good infectious disease to drill for because there is so much that is still unknown about it. For example, the method of transmission between humans is poorly understood. One human can infect another, but the exact route has not been confirmed. In addition, even the current mortality rate of around 30% for MERS is uncertain because scientists now think some people with MERS may be asymptomatic, Olival says.

MERS as it initially presents looks much like any severe acute respiratory illness with symptoms of fever, cough and shortness of breath. That is why getting a patient’s travel history is so important. Some patients also may have diarrhea and nausea/vomiting. For many patients, severe complications such as pneumonia and kidney failure then develop.

In the cases observed so far, people with other conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and chronic lung, heart, and kidney disease were the most likely to die. Since hospitals treat many such patients, preventing the disease from spreading within a hospital setting is key.

Stopping the Spread of MERS

Alberts notes that one should think carefully about the placement of the positive pressure room in facility design and how the patient will be moved within the hospital, for example, from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Respiratory therapists who may be involved in treatments such as sputum induction or open suctioning of airways that might aerosolize the virus should use special precautions, CDC guidelines say. During such procedures, the patient should be in a private room, ideally in an airborne infection isolation room with positive airway pressure.

The doors should be kept closed with entering and leaving kept to a minimum during and immediately after the procedure. Only healthcare personnel necessary for care and comfort should be in the room and they should wear gloves, a gown, and either a face shield that fully covers the front and sides of the face or goggles, and respiratory protection that is at least as protective as a fit-tested N95 filtering facepiece respirator (e.g., powered air purifying or elastomeric respirator).

Because the disease does not seem to spread among people before symptoms develop, CDC guidelines note that healthcare personnel who have unprotected exposure to the symptomatic patient with MERS may continue working if there is a shortage of personnel, provided they take precautions such as wearing a mask.

However, if there is not a shortage of personnel, the safest course is to have the possibly exposed care team members stay home for the 14-day incubation period for MERS. That is what Dr. J. Philips Hospital staff who had unprotected exposure to its MERS patient did. None of them ended up developing MERS, but the hospital paid them to stay home and used a vehicle from Occupational Health to test them to avoid having them reenter the hospital for their testing.

Even though the patient was identified relatively quickly, tracking all the potential exposures was one of the big challenges, Alberts says. The hospital used emergency department logs to identify who was in the emergency department waiting room at the same time as the patient and asked these people to recall exactly where they had been seated.

Because the first person the patient encounters upon arriving at your healthcare facility may be a non-clinician, empowering everyone, regardless of his or her role to speak up about something suspicious is key. Crespo says he gets regular calls about patients with possible rare infectious diseases, such as MERS and now Ebola, and that is a good sign.

“It is a matter of creating a culture of awareness that goes all the way from the security guard who may be the first to talk to the patient when he comes to the emergency department, to the physician,” he says. “It comes from the constant reminders, the drills and the other things we’ve been doing . . . I believe our team members feel very safe [speaking up], and we want to continue to nurture that.”

The same goes for other healthcare providers. Crespo says that when Dr. J. Philips Hospital realized it had a patient with MERS, it reached out to the CDC, the hospital in Indiana with the other MERS patient, and other experts for advice and guidance. He urges any institution that sees a MERS patient in the future to do the same. “Just call for help, we have this experience and we would be happy to help,” he says.

RT

Greg Thompson is a contributing writer to RT. For more information visit [email protected].

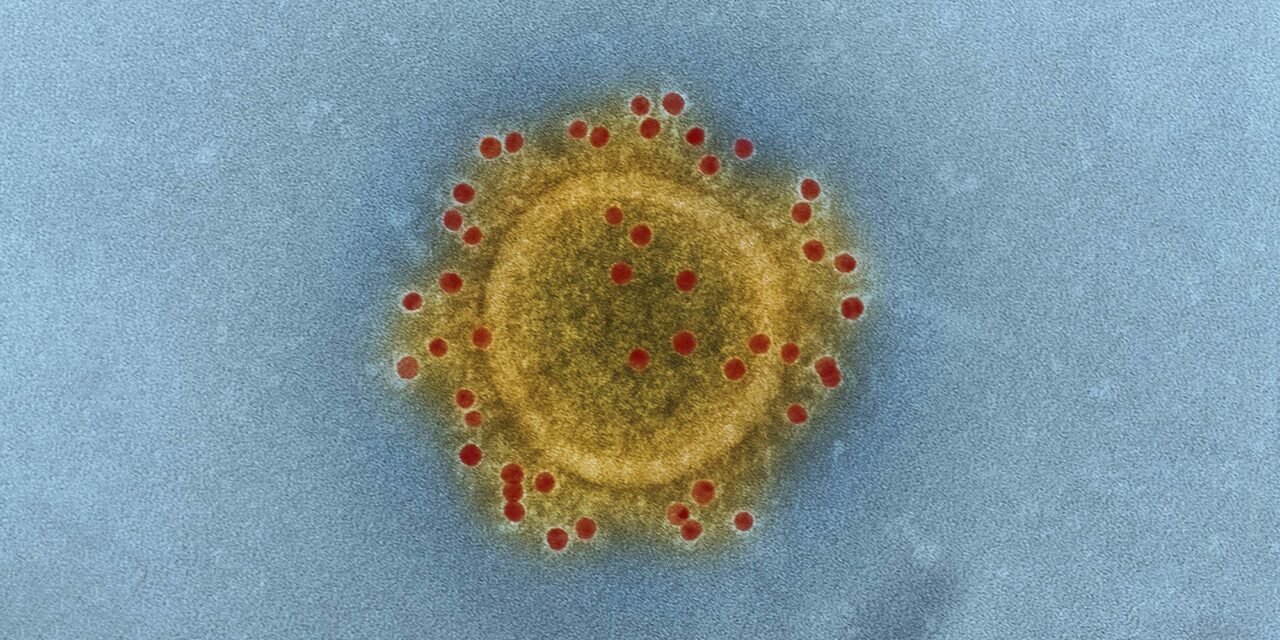

Image: MERS Coronavirus Particle & Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus particle envelope proteins immunolabeled with Rabbit HCoV-EMC/2012 primary antibody and Goat anti-Rabbit 10 nm gold particles. Original image sourced from US Government departmen [sic]. Free download under CC Attribution (CC BY 4.0). Please credit the artist and rawpixel.com.Virus Electron Micrographs from US Government department: The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). This Novel Coronavirus collection includes the COVID–19 virus and other pandemic viruses. They are free to download under the CC0 license. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus particle envelope proteins immunolabeled with Rabbit HCoV-EMC/2012 primary antibody and Goat anti-Rabbit 10 nm gold particles. Credit: NIAID