New Jersey Health Foundation (NJHF) has awarded NJIT engineer Eon Soo Lee a $50,000 Innovation Grant to develop a nanotechnology-enhanced biochip that would give doctors and patients in a range of healthcare settings the ability to detect deadly diseases such as ovarian cancer and pneumonia early in their progression.

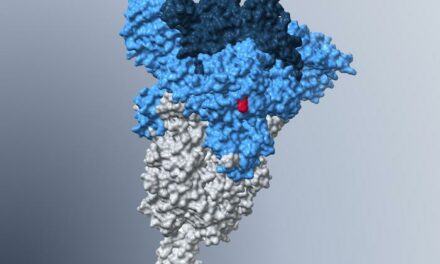

The device includes a microfluidic channel through which a tiny amount of drawn blood flows past a “sensing platform” coated with biological agents that bind with antigens – biomarkers of disease that elicit an immune response by the body – thereby triggering an electrical nanocircuit that signals their presence.

The chip’s biosensors are “highly sensitive to small amounts of very specific antigens,” explained Lee, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering, who added that a single biochip’s platform could potentially include sensors for several diseases, from cancers to viral infections.

The technology is being designed for use by specialists and primary doctors and, Lee hopes, healthcare workers in remote clinics in developing countries who can administer the tests with a simple finger prick.

“As we know, early detection can improve treatment outcomes for patients significantly,” explained George F. Heinrich, M.D., vice chair and CEO of NJHF, a not-for-profit corporation that supports biomedical research and health-related education programs in New Jersey. “Currently, doctors rely on diagnostic devices requiring a minimum of four hours of sample preparation through centralized diagnostic centers rather than their local offices. We are interested in Dr. Lee’s project because the biochip he is developing would provide instant results at a local office or point of care without needing sample preparation.”

If successful, the biochip will expedite the diagnosis of diseases including viral infections such as HIV, sexually transmitted diseases and toxoplasmosis and cancers such as prostate, liver and thyroid cancer.

Lee is now working with oncologists at Hackensack Medical Center who care for women with ovarian cancer – often undetectable until it has reached a late stage that is difficult to treat – to develop and test the technology. “Screenings for ovarian cancer are often cumbersome and uncomfortable,” Lee noted.

The biochip is designed to reduce the possibility of sample contamination by minimizing the need for flow control devices and connecting tubes. It analyzes a tiny amount of blood within two minutes without any external devices.

One of the device’s core innovations is the ability to separate blood plasma from whole blood in its microfluidic channels. Blood plasma carries the disease biomarkers and it is therefore necessary to separate it to reduce detection “noise” in order to achieve a highly accurate test, Lee explained.